Pre-season assessments and monitoring: are returning athletes ‘strong enough’ to run fast?

Available in:

EN

Alex Natera

Alex is Manager of Performance Support at the New South Wales Institute of Sport, where he oversees a department of 40 world-class practitioners across Strength and Conditioning, Physiology, Psychology, Nutrition, Biomechanics and Performance Analysis disciplines.

Alex’s background in Strength and Conditioning spans nearly 25 years in professional sports and National institutes of sport across the globe. Alex is also a highly sought-after speaker and educator, consulting with clubs, elite individual athletes, and support staff from the EPL to the NBA.

In this article, Alex discusses the importance of early pre-season assessments and screening in determining the physical status of the playing group and the individual. He provides an introduction to his Run-Specific Isometric Assessment Battery, which uses ForceDecks to perform the Ankle Iso-Push, Knee Iso-Push, and the Hip Iso-Push.

This battery is an ‘under-the-hood’ look at whether players are returning strong enough to run fast, and can be used to establish the magnitude, rate, and extent to which players can be loaded leading up to the start of competition.

Pre-season assessments and monitoring: are returning athletes “strong enough” to run fast?

You are a couple of weeks out from the players returning from their off-season break. The performance team are meeting to iron out the preseason plan and determine what the first couple of weeks of training will look like for the entire playing squad and specifically for various members of the squad. The performance team are crossing their fingers and hoping that the players were diligent and compliant with their offseason training programmes.

The reality is, even at the very top end, only a small portion of the squad will have accomplished what you set out for them to achieve over the off-season. Despite this, even if they did execute the off-season plan, to a tee, it is unlikely the loads they experienced will match or surpass what they will need to experience throughout preseason and into the competitive season.

The reality is, even at the very top end, only a small portion of the squad will have accomplished what you set out for them to achieve over the off-season.

There are the usual nerves around certain players (“frequent offenders”) and so the performance team agrees to start week 1 preseason with loading that caters for the lowest common denominator. The “loading clock” then starts ticking down from session 1 to the first preseason game and the pressure is on. If you push them too hard and too soon, you risk breaking them, but if you don’t push them hard enough, game loads and back-to-back games eventually will. If you don’t start meaningful work early enough you’ll run out of time or you’ll run the risk of not allowing sufficient recovery and regeneration within your preseason and again there is the chance they will break.

If you push them too hard and too soon, you risk breaking them, but if you don’t push them hard enough, game loads and back-to-back games eventually will.

Early preseason becomes critical to determine the physical state of players as they return. It presents an ideal opportunity to assess the physical status of the playing group as a collective and, importantly, for the individual. Depending on the sport and the length of the off-season it might also be a period of time where fatigue is at its lowest point and niggles carried through the previous season can somewhat settle. Collecting assessment data is essential during this part of the year, to establish baselines and to determine current status from which to load.

The challenge for most performance teams is time and the “time-tug-of-war” between the sport coaches demands and the performance team’s needs. Some teams are fortunate enough to be able to negotiate and establish clear blocks of time early in pre-season where they conduct their screening and assessments. Others don’t have the buy-in, collaboration and support and therefore squeeze whatever they can in, whenever they can. Often in these environments the datasets are incomplete, unreliable, messy and – in some cases – not really useful at all. Pre-season assessments and screening in these environments become a “tick box exercise”, and sadly everyone can sense it – including the players.

Pre-season assessments and screening in these environments become a “tick box exercise” and sadly everyone can sense it – including the players.

High Performance Managers – who establish strong and trusting relationships and have the ability to influence Head Coaches – are critical in balancing the needs of both parties in this scenario. Strategically embedding pre-season assessments and screening within the training week has often been a fantastic middle ground for most teams. The planning, the sell, the execution and the follow up of this to players and coaches can make or break the success and effectiveness of pre-season assessments and screening moving forward.

Preseason high speed running: risk vs. reward

In pre-season planning, all facets of load are important to consider, from strength training intensity, plyometric volume and eccentric exposure to running volume, change of direction count and the magnitude of collisions, to name a few. One of the most important load factors to consider is the intensity, volume and density of “very high speed” and maximal speed running (herein referred to as “high speed running” [HSR]). Walking the fine line of not too fast, not too much, not too often and not too soon have made many a performance coach lose sleep at night.

One of the most important load factors to consider is the intensity, volume and density of “very high speed” and maximal speed running. Walking the fine line of not too fast, not too much, not too often and not too soon have made many a performance coach lose sleep at night.

During HSR, lower limb muscle groups produce very high forces at very high rates:

- Swing phase: the hip flexors and the hamstrings can produce muscle forces up to ~10 x Body Weight (BW).

- Stance phase: muscle force production can be up to ~10 x BW for the plantar flexors and ~5 x BW by the quadriceps (Dorn et al. 2012).

- Ground reaction forces: can be up to 4 x BW and occur in less than 100ms (Weyand et al., 2010).

HSR, particularly in a training format, is a potent stimulus to the neuromuscular system. Significant central and peripheral fatigue have been observed after HSR sessions and even with relatively low volumes, several days are required to fully recover (Johnstone et al. 2015; Thomas et al. 2018). Due to these and several other biomechanical and physiological demands, HSR is a significant risk factor in soft tissue injuries (Gabbet et al. 2012; Duhig et al. 2016; Chavarro-Nieto et al. 2023).

Therefore, the careful planning of HSR exposure in the pre-season is critical. Where you can start and where you can go with your players often comes down to what HSR exposures (intensity, volume, density, frequency and type) were achieved during the off-season period. Despite this, the de-load experienced in the off season often means the regression or degradation of certain physical qualities. With the muscular forces and ground reaction forces seen in HSR, the notion of being “strong enough to run fast” needs to be seriously considered along with HSR exposure.

With the muscular forces and ground reaction forces seen in HSR, the notion of being “strong enough to run fast” needs to be seriously considered along with HSR exposure.

Early pre-season assessments of both maximal and rapid force development of the lower limbs are essential to understand the requisite force generating capacities of key muscle groups involved in HSR. As addressed earlier, the early preseason period provides an opportunity to establish baselines but also to compare with in season/previous season values and assess the magnitude or otherwise of degradation. In my opinion, “earning the right to run fast” is a combination of graded, specific HSR exposure and developing or retaining the underpinning force generating qualities to be able to handle the forces experienced in HSR.

…“earning the right to run fast” is a combination of graded specific HSR exposure and developing or retaining the underpinning force generating qualities to be able to handle the forces experienced in HSR.

The isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) presents a proven, reliable, effective and long-standing assessment of maximal force and rapid force generating qualities. The IMTP and its close cousin, the isometric squat assessment, are excellent assessments which practitioners can administer safely in early pre-season to establish force generating qualities of the lower limb. In comparison with the risk of maximal strength testing returning players both assessments are certainly the preference.

However, despite being effective general force assessments, they lack the specificity to identify force generating capabilities of specific muscle groups at the specific muscle lengths used in HSR. Assessing positions and postures resembling HSR positions and postures, whilst more effectively isolating key muscle groups around the ankle, knee and hip joints are becoming more popular in high performance settings. In doing so, we can collect more information to make more informed decisions around whether and when players are in fact “strong enough to run fast”.

Earning the right to run fast with Run-Specific Isometrics

Importantly, the Run-Specific Isometric assessments are multi-joint assessments, despite each individual assessment’s name. They do not strictly isolate the force generating capabilities of a single joint.

Over the course of my career I’ve developed one such assessment protocol, which I call the Run-Specific Isometric Assessment Battery, made up of the Ankle Iso-Push, Knee Iso-Push and the Hip Iso-Push.

These assessments are similar to the joint positions found in mid-stance of the HSR stride. Importantly, the Run-Specific Isometric assessments are multi-joint assessments, despite each individual assessment’s name. They do not strictly isolate the force generating capabilities of a single joint. The Run-Specific Isometric assessments are designed to bias a joint and this is where we infer the force-generating capabilities of the muscles surrounding the target joint. The Run-Specific Isometrics assessments are all performed unilaterally to further elucidate any inter-limb discrepancies and asymmetries.

Ankle and Knee Iso-Push

Both the Knee and the Ankle Iso-Push are performed in an upright, standing position. For these assessments, I use VALD’s ForceDecks and isometric squat rack. However, these tests have also been performed using overloaded barbels resting on the pins or barbells pushed under the pins of a racking system.

The Knee and Ankle Iso-Push are performed with the bar on the upper trapezius muscles, as in a high bar squat set up. In the Knee Iso-Push, the mid-foot of the tested leg is placed directly under the bar and the knee and hip angles are between 135-145° and 160-170°, respectively. In the Ankle Iso-Push, the ball of the foot of the tested leg is placed under the bar to facilitate a slight forward lean. In this assessment, the knee and hip are fully extended, and the ankle positioned between neutral and 10° of plantar flexion.

Hip Iso-Push

In the Hip Iso-Push the athlete lies supine on the floor with the inferior portion of their shoulder blades resting on a comfortable 15cm box. The heel of the testing foot is placed on the force plates and an immoveable bar is positioned at their hip crease. The knee and hip angles in the Hip Iso-Push resemble that of the Knee Iso-Push (135-145° and 160-170° respectively). Importantly, we measure these angles when the athlete lifts their hip from the floor and presses them into the bar.

Warm Up and Test Protocol A general warm up is conducted before the assessments and a specific warm up is performed for each assessment immediately before the test:

- Specific warm up: 3 x 3 second efforts at 70%, 80% and 90% effort with 10 second recovery between efforts.

The athlete then rests for 60 seconds before performing either a rapid force assessment or a maximal force assessment.

- Rapid force assessments: 5 x 1 second efforts interspersed with 10 second recovery.

- Maximal force assessments: 2 x 3 second efforts with a 2 second “build up”.

Each effort is followed by a 60 second rest. A third trial is then performed if the second trial is >3% of the first trial. Generally relative peak force is captured and reported for maximal force trials and force at 100 ms for rapid force trials.

Interpreting the Results

Although normative data are used to guide and compare male and female team sport athletes, in the context of being “strong enough to run fast” it is also important to assess each athlete against their previous seasons’ results.

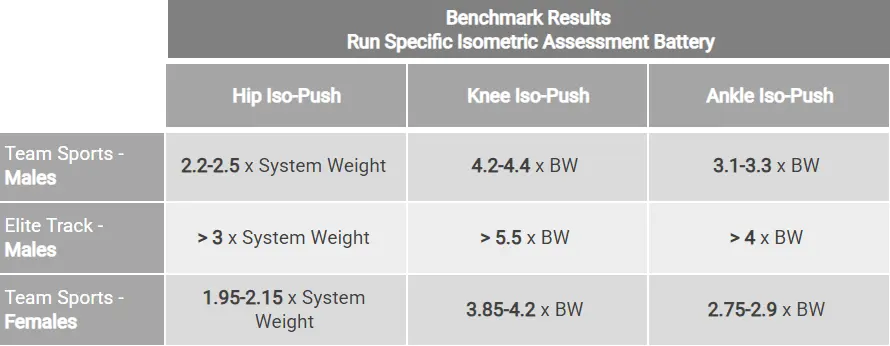

As a rough guide, “Good” results for female team sport athletes for a Hip Iso-Push would be ~1.95-2.15 x system weight (the system weight is the amount of body weight supported at the heel in the supine bridge type position [~25% of body weight], Knee Iso-Push ~3.85-4.2 x BW and Ankle Iso-Push ~2.75-2.9 x BW.

For male team sport athletes, a good Hip Iso-Push would be 2.2-2.5 x system weight, Knee Iso-Push 4.2-4.4 x BW and Ankle Iso-Push 3.1-3.3 x BW. For comparison, elite male track athletes can attain Hip Iso-Push scores of >3 x system weight, Knee Iso-Push scores of >5.5 x BW and Ankle Iso-Push scores of >4.0 x BW. It is very rare for team sport athletes to hit these values but what this does show is that there is plenty of room to improve in strengthen the key muscles for HSR.

Applying the Results

Over an off-season period of 4-8 weeks, it is not uncommon for a team sport athlete to drop between 0.25-0.5 x BW maximal force in the Knee and Ankle Iso-Push, for example. Regaining this strength is paramount and should be prioritised along with the introduction of progressively increasing HSR exposure and plyometric progressions.

Just as important is attaining previous levels of force at 100 ms. With brief ground contact times during HSR it is arguably more important to either produce high rates of force or a greater proportion of maximal force in that brief time period. Very explosive athletes can produce up to 80% of their maximal force in 100 ms and less explosive athletes <60%. Again, what is most important in the returning athlete is to regain their previous season values to “earn the right” to run fast.

Over an off-season period of 4-8 weeks it is not uncommon for a team sport athlete to drop between 0.25-0.5 x BW maximal force… Regaining this strength is paramount and should be prioritised.

Performance teams can use the Run-Specific Isometric Assessments embedded within the preseason week 1 schedule to determine the HSR starting point and progression rates of each of their players.

In the simplest terms, if a fit returning player has had good HSR exposure through the off season and returns with maximal force and rapid force scores within their normal range, a more regular or even aggressive HSR approach might be warranted. If a player returns having achieved the planned high speed running exposures over the off season, is within their range of their previous maximal force values, but fails to attain their previous force at 100 ms, then a more cautious HSR loading scheme might be planned. Clearly, if a player has not had HSR off season exposures and fails to attain within range maximal force or rapid force levels then a conservative loading approach is likely to be planned.

Clearly, if a player has not had HSR off season exposures and fails to attain within range maximal force or rapid force levels then a conservative loading approach is likely to be planned.

In summary, the early preseason is a critical time to establish normative assessment and screening data for your players. The information provided can be used to identify the magnitude, rate and extent by which you can load your players leading to the start of competition. Earning the right to run fast is determined through HSR exposures and also through the current force generating capabilities of the key muscles used in HSR. The Run-Specific Isometric Assessment Battery provides a good ‘under the hood’ look at whether your players are returning strong enough to run fast.

If you would like to know more about how to integrate VALD’s human measurement technology into your organisation to help with the engagement of your clients, please reach out here.

References

- Dorn TW, Schache AG, Pandy MG. Muscular strategy shift in human running: dependence of running speed on hip and ankle muscle performance. J Exp Biol. 2012 Jun 1;215(Pt 11):1944-56. doi: 10.1242/jeb.064527. Erratum in: J Exp Biol. 2012 Jul 1;215(Pt 13):2347. PMID: 22573774.

- Weyand PG, Sandell RF, Prime DN, Bundle MW. The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2010 Apr;108(4):950-61. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00947.2009. Epub 2010 Jan 21. PMID: 20093666.

- Thomas K, Brownstein CG, Dent J, Parker P, Goodall S, Howatson G. Neuromuscular Fatigue and Recovery after Heavy Resistance, Jump, and Sprint Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018 Dec;50(12):2526-2535. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001733. PMID: 30067591.

- Johnston M, Cook CJ, Crewther BT, Drake D, Kilduff LP. Neuromuscular, physiological and endocrine responses to a maximal speed training session in elite games players. Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;15(6):550-6. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2015.1010107. Epub 2015 Feb 12. PMID: 25674673.

- Gabbett, Tim J; Ullah, Shahid. Relationship Between Running Loads and Soft-Tissue Injury in Elite Team Sport Athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 26(4): p 953-960, April 2012. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182302023

- Duhig S, Shield AJ, Opar D, et al. Effect of high-speed running on hamstring strain injury risk. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016; 50: 1536-1540.

- Christian Chavarro-Nieto, Martyn Beaven, Nicholas Gill & Kim Hébert-Losier (2023) Hamstrings injury incidence, risk factors, and prevention in Rugby Union players: a systematic review, The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 51:1, 1-19, DOI: 10.1080/00913847.2021.1992601